UPDATE: President Barack Obama has commuted the sentence of Chelsea Manning, which is now set to expire on May 17. The decision wasn’t a total surprise, as a White House spokesman had contrasted Manning’s situation with Edward Snowden, noting that Manning already has gone through the U.S. legal system and acknowledged her crimes. In all, Obama granted commutation of sentence to 209 individuals and pardons to 64 individuals.

President Barack Obama has less than a week left to make at least some small amends for his administration’s war on government whistleblowers. And right now, across the broad spectrum of social media, members of the public and the media are specifically requesting that Chelsea Manning be granted presidential clemency. This renewed attention — which sprang from Twitter in the form of various hashtags including #FreeChelseaNow and #HugsFor Chelsea, as well as via myriad op-eds penned by the likes of Colonel Morris D.Davis, journalist and lawyer Glenn Greenwald, and Chelsea Manning herself — all has to do with the fact that Obama’s tenure in office will come to a close in three days — possibly taking it with the former Army intelligence analyst’s chances of freedom if he doesn’t act now. Manning was arrested in 2010 for leaking U.S. diplomatic cables to WikiLeaks. Two years later, she plead guilty to 10 of the 22 charges against her, some of which included violations of Articles 92 and 134 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), and of the Espionage Act. On Aug. 21, 2013, she was sentenced to 35 years in prison — the longest sentence ever imposed for disclosing government secrets.

At the time, Chelsea was known as Bradley Manning. On August 22, 2013 — the day after her sentencing — Manning’s then-attorney David Coombs issued a press release announcing that his client identifies as female, and asked that she be referred to by her new name of Chelsea and with feminine pronouns. Now at stake is the very real possibility that Manning may not be able to live as “the person she was born to be” — a turn of phrase she herself emphasized in a Nov. 18, 2016 public plea to President Barack Obama.

I reached out to Manning’s ACLU attorney, Chase Strangio, for his thoughts on what Manning’s life might be like should President Obama leave the former U.S. intelligence analyst’s fate to the whims of a Trump administration.

“She has already been through long periods of solitary confinement, been denied medically necessary care prescribed by her military doctors, and attempted suicide twice in the past six months,” Strangio told me. “Her access to treatment may be further jeopardized by the incoming administration and I fear for her well-being should any federal policies on access to health care for transgender people be revoked or changed.”

Strangio has good cause to be concerned. Though Manning was granted gender confirmation surgery in September 2016 as part of the U.S. military’s broader policy change that allows transgender servicemembers to serve openly and to receive coverage of their medical care, these protocols could potentially soon be overturned under President Donald Trump. In October, the president-elect vowed to review the military’s new policy on transgender service-members, calling it “a dangerous act of political correctness.” Furthermore, the man Trump nominated to be his national security advisor, Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, alluded to the policy during his speech at the Republican National Convention last July, suggesting that it was “distracting the troops from their mission.”

“It would be a devastating blow to her if nothing happens at this point and she is left looking again at decades in prison —under possibly worse conditions.”

And, as Strangio mentioned, Manning has previously made two suicide attempts. After she first tried to end her life last July, the military responded by bringing additional charges against her for “resisting the force cell move team,” even though, as Strangio has claimed on numerous occasions to the media since, she was unconscious at the time. An Army board then decided to throw her into solitary confinement for her suicide attempt before she was able to appeal those charges — a response Strangio considered “demoralizing” and told the AP as much. He added that solitary confinement was an “assault on her health and humanity.” Indeed, once isolated Manning attempted suicide a second time. (I reached out to The United States Disciplinary Barracks for comment but the facility did not respond.)

There has been a slight glimmer of hope for Manning in recent weeks. On Jan. 11, NBC News reported that she is indeed on President Obama’s “short list” for sentence commutation after a petition with more than 100,000 signatures met the threshold for a White House response within 60 days. The American Civil Liberties Union and gay-rights groups have likewise been lobbying for a reprieve, citing Manning’s need for better medical care for gender dysphoria, a condition that includes severe distress or anxiety for some transgender individuals. While news of the “short list” elicited some excitement and hope from both the public and the media, the president has yet to officially make that a reality.

Now, as Strangio tells it, “Chelsea is taking everything in stride, but of course is nervous and it is impossible for her not to feel hopeful hearing the recent reports from the White House and DOJ officials. It would be a devastating blow to her if nothing happens at this point and she is left looking again at decades in prison — under possibly worse conditions.”

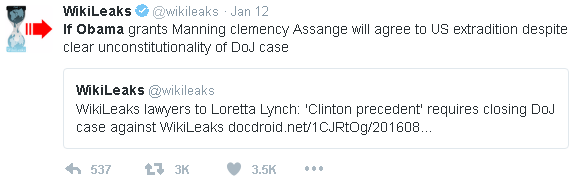

Several others have taken up Manning’s cause in the meantime, including whistleblower and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who agreed to be extradited from Ecuador to the United States to face possible espionage charges if POTUS pardons Manning.

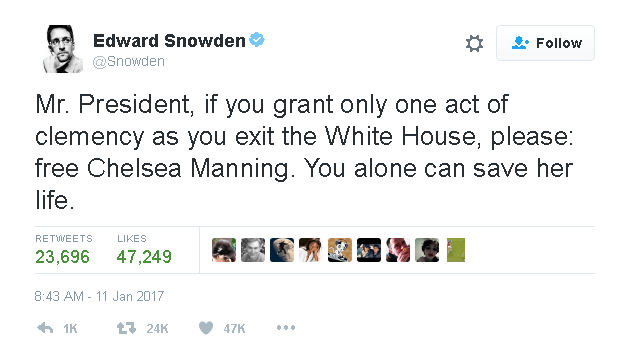

Former National Security Agency (NSA) analyst Edward Snowden, too, has reached out to Obama’s administration on Manning’s behalf. Snowden, who has been in Russia since 2013, when he leaked classified information from the NSA revealing illegal U.S. mass surveillance, called on POTUS to grant Chelsea Manning clemency — even over himself. The particulars of Snowden’s case, however, are quite notably different than those of Manning’s. For one, Snowden is not in prison; two, his identity as a human being is not at immediate risk.

As was the case with the petition prompting the White House’s response, anyone interested in voicing their concerns about Manning’s fate can make a difference. To offer your help, call 202-353-1555 (DOJ comment line) and follow this simple script:

“Hi, I’m [NAME] from [STATE] and I’d like Chelsea Manning’s sentence to be commuted to time served.”

Image: Wikicommons/Abby Higgs